The algorithm has become the retina of the mind’s eye.

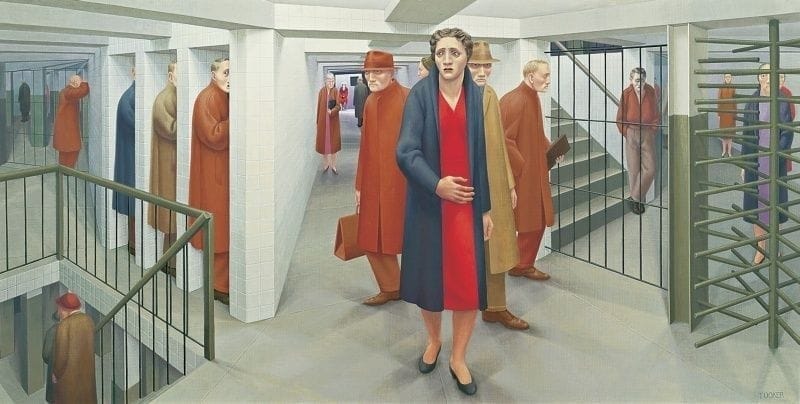

George Tooker, The Subway, 1950

So much went wrong over the election— plenty of blame to go around — but today, my focus is on one culprit: algorithms.

The 2024 election wasn’t just a political event; it was an algorithmic disaster.

Democrats were stunned as red swept across the map, with Trump retaking the presidency. By the next day, pundits pivoted into told-you-so mode. But we, the viewers of America’s final season, remember their pre-election thinkpieces. It’s like they were living in a parallel reality. And they were. We all are.

Though the world feels bigger than ever, our experiences are more atomized. We’ve all got our own unique information diets — and like all diets, they’re tailored to taste. Algorithms are the special sauce that keeps everything palatable, just spicy and varied enough. They dominate our perceptions, shaping everything we see across the platforms we use daily.

Neil Postman warned us decades ago in Amusing Ourselves to Death that entertainment media would distort public discourse. More recently, Kyle Chayka, in Filterworld, described how algorithms flatten culture, reducing it to simplest, most engaging parts — turning everything into a personalized feed. Both dynamics worked at once to radicalize disconnected groups and blind elites.

The result is a a fragmented, myopic electorate where everyone sees only what they “want” to see — or what an algorithm decides they should see.

Forget filter bubbles. We’re soaking in filter bubble baths now. The water’s warm.

“Filter bubble bath” courtesy DALL-E

TikTok, propaganda, and the Manosphere

Let’s talk about the Manosphere, which WIRED defines as “the amorphous assortment of influencers who are mostly young, exclusively male, and increasingly the drivers of the remaining online monoculture.”

One key post-election is narrative is how men — young, uneducated men, in particular — have been pushed to the right through misinformation and propaganda filtered to them via Joe Rogan and the like. On The Media did a great deep dive into this ecosystem. In it, they lament our new media environment:

The news monoculture of old is dead… the new administration has shown us that it will learn on a new generation of personalities and media networks to spread its lies and shape hearts and minds.

It’s a persuasive argument. Max Read’s great piece on “The TikTok Electorate” adds a critical nuance: TikTok and other social media aren’t solely to blame.

When you rely too much on the idea that propaganda works homogeneously and omni-directionally, it’s very easy to misdiagnose the problem. Is Andrew Tate really turning innocent, smooth-brained young morons into misogynists all on his own? It seems much more likely that some young men bring a set of misogynist assumptions and masculinist entitlements to TikTok and YouTube, and have those self-flattering ideas reinforced and strengthened into hardened beliefs.

Algorithms amplify what’s already there. The solution, then, isn’t to launch a liberal version of Joe Rogan, but to address misogyny at its roots. As Jia Tolentino points out, young men have long been fighting for relevance in a ‘gender war.’ Their sense of loss could help explain why men aged 18–29 have shifted 30 points rightward since 2020.

The fact remains that a large swath of young men isn’t participating in the same information ecosystem as the rest of us. They have their own channels, their own realities, nearly independent from ours. Our tweets won’t save them — or sway them.

The à la carte electorate

AOC’s election-night Instagram polls provide another interesting case study of how algorithmic-inflected behavior might result in ticket-splitting. As it turns out, she has a growing group in her district of people who voted for Trump and her. She asked them why:

via AOC’s Instagram

Both AOC and Trump are seen as “real” and “anti-establishment.” Both care about the working class. Both promise change. Crucially, neither was tied to the current administration. In a filtered world, these politicians don’t feel opposed; they feel like two sides of the same coin.

This kind of ticket-splitting defies conventional political logic, but in the algorithmic age, it makes perfect sense.

Younger voters, conditioned to an algorithmic existence, maybe approach elections like their social media feeds: fragmented and hyper-personalized. They curate ballots, selecting candidates based on personal resonance rather than party loyalty. It’s a “choose-your-own-adventure” style of politics, where down-the-line voting isn’t the default.

The algorithmic medium is the message

I want to push this idea bit further. I believe we’re living in a broad social experiment whose consequences we won’t understand for some time.

Media theorist Marshall McLuhan famously posited that “the medium is the message.” He meant that the medium itself — TV, video, a social feed — shapes human thought more than the content it delivers. Neil Postman expanded upon this idea, arguing that in a TV-dominated society, serious topics are simplified into entertainment. Public discourse shifts from logic-driven to spectacle-driven. (Is it any surprise that TV-star Trump is a repeat president?)

What is the ‘message’ of the algorithmic feed? What does it do to its users?

Here’s how I see it:

Information must be entertaining: Users expect even run-of-the-mill information to be engaging.Successful messages have successful messengers: Parasocial relationships are highly effective.Simple ideas fly far: Algorithms prioritize emotionally resonant, easy-to-digest content.Content is participatory: Likes, swipes, and other signals shape what users see. The content feels co-created by viewers, giving them ownership of it.

Trump and AOC win feeds. Both exude authenticity, a currency that platforms — and voters — reward. Both have simple ideas told in engaging ways (with Trump’s obviously leaning hard into fear, sexism, and xenophobia). Both offer a way for their viewers to participate. AOC sparked this great discussion via Instagram poll.

Meanwhile, establishment figures falter. Their campaigns feel stiff, lecture-like, and their complex ideas struggle to break out of their bubbles.

Max Read argues that these platforms change users in a deeper way: they condition users to embrace volatility. TikTok’s feed is a chaotic blend of hits and misses, encouraging a speculative, gamified mindset. The result is a generation of voters who approach politics like a gamble, chasing high-stakes wins with little regard for long-term coalition-building.

Whose race is it, anyway? via Reductress

The algorithm has become the retina of mind’s eye

In Cronenberg’s “Videodrome” (1983), Marshall McLuhan’s ideas reach an eschatological extreme. The film shows a world addicted to television, where media rewires viewers’ minds, leading to hallucinatory ultraviolence. It’s a trip.

One of my favorite quotes comes from the film’s Professor Brian O’Blivion, a “media prophet,” who declares that “television is the retina of the mind’s eye.”

In 2024, that retina is algorithmic. Algorithms don’t just shape what we see; they shape how we see, what we imagine, and how we empathize with others.

This election showed us what happens when millions of individual, algorithm-curated realities collide. The result isn’t just political polarization; it’s the erosion of a shared cultural and political context. Rebuilding that context will require more than just better messaging. It demands a reckoning with the structures — both digital and social — that shape our perceptions. Until then, we’ll remain stuck in our own personalized feeds, wondering why everyone and everything feels so incomprehensible. — XML

FROM MY FEED

Neal Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death and Kyle Chayka’s Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened CultureMax Read on “The TikTok Electorate” (via his substack); Jia Tolentino on “How America Embraced Gender War” (The New Yorker); Brian Barrett on “The Manosphere Won” (WIRED).On The Media looks at the Manosphere (listen)“Medium Cruel: Reflections on Videodrome” (Criterion)Han Kang’s The Vegetarian, trippy ecofeminist fable and recent Booker recipient

The Algo election: how 2024 revealed a fragmented reality was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.