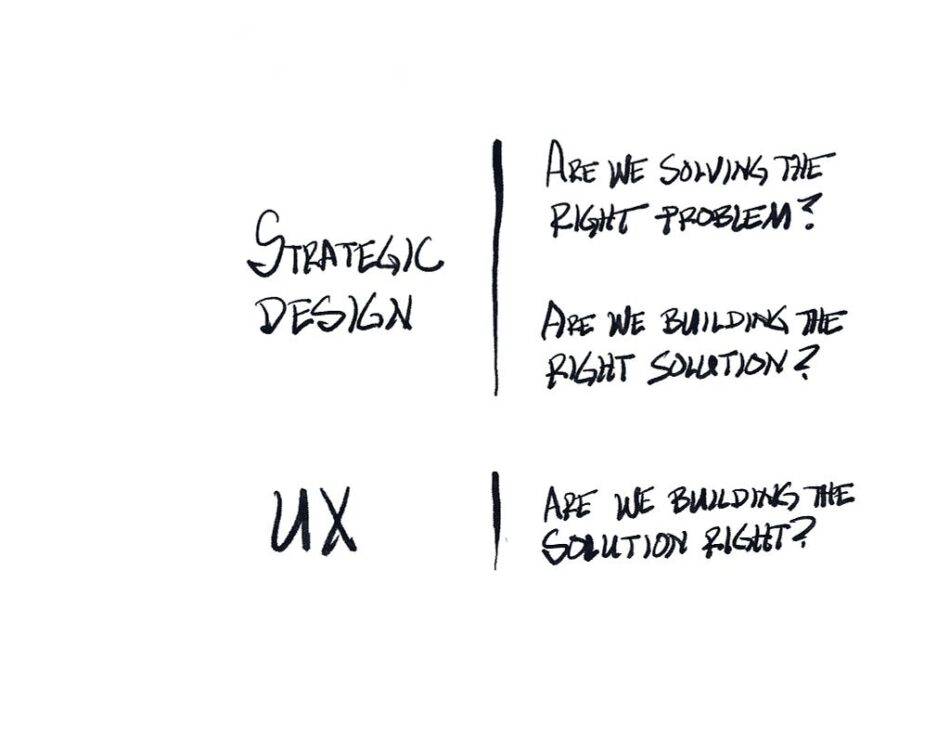

Design Strategy

Leverage strategic design to understand deeper customer needs and ensure you’re building the right solution, not just building the solution right.

The most important role a design strategist has in an enterprise is to own two questions:

1. “Are we solving the right problem?”

2. “Are we building the right solution?”

Both of these questions are essentially ways of mitigating business risk. And both are well upstream of modern product development processes, which are concerned not with “Are we building the right solution?” but “Are we building the solution right?”

Solving the right problem can feel superfluous to the day-to-day business/product treadmill. But it’s critical to maintaining a competitive position in an ever-changing market, and it’s the only place where the most interesting new opportunities and ideas are to be found.

I often share a personal case study to illustrate this.

The Brief: In 2017, an Australian real estate developer engaged me to help them crack a problem that had been vexing them for years. This company built large residential properties around Melbourne, with an eye primarily to property investors. As it happened, most of their buyers were residents not of Australia but of Shanghai, Singapore, Hong Kong, Kuala Lumpur, and Bangkok. To sell to these overseas investors, the company had a raft of foreign ‘middle agents’ in each city who knew the local culture and the language, facilitating sales between the developer’s own Melbourne agents and the local populations.

I’d been brought in because the CEO of the company had realized he was sinking millions of dollars into these middle agents for each residential project, and he wanted to reclaim that money. My brief, in brief: find a way to eliminate the middle agents without impacting offshore sales.

Ultimately, I did not solve that problem. But that’s not because I failed. It’s because it was the wrong problem.

A Horizontal Skillset

The roles and skills a design strategist brings to any given project are decidedly T-shaped. Many strategists emerge from traditional product leadership pathways, to be sure. But some of the most effective strategists bring very different professional backgrounds to this role, often well outside the arena of design; the best tend to be generalists, not specialists.

First, a design strategist needs to know the language and mechanics of business. They’re working to advance business objectives for the org at the highest level, not simply running a feature factory on an existing product. At minimum, they know the most common business models inside and out, and can generate and assess variations on these. At more senior levels, they understand how to plan and validate a new venture, product or service that solves a well-understood problem for a target segment, estimate its potential business ROI, and create a rigorous plan for iterative prototyping, deployment, and measurement.

A strategist must be a deft hand with ethnographic field research. They’re digging broader and deeper than merely the pain points on current products, instead exploring higher-order experiences — e.g. what Jared Spool calls “deep hanging out sessions” — collecting observations and insights that show what a day in the life of users could be. Even if they’re not doing the research themselves, they’re able to synthesize the results — often in combination with quant data — for the non-obvious gold that points to intriguing new insights and opportunities.

The most effective design strategists are T-shaped generalists who wear many hats. Though an individual’s expertise many not be equally distributed, great strategic teams assure mastery across them all.

Working across silos and business units with myriad cross-functional stakeholders at every level means strategists must also be canny, persuasive diplomats, securing buy-in and, often, articulating and evangelizing for a customer-first approach across the org. This calls for adept and holistic systems thinkers.

A strategist will be a savvy facilitator, planning and leading productive, outcome-oriented design sessions. She’ll also be an accomplished storyteller who uses language, sketches, graphics, and any other medium at hand to show instead of tell, visualize abstractions, and help us empathize with users.

If this all sounds like the description for a mythical professional “unicorn,” you’re not wrong. Few but the most senior design strategists will confidently wear every one of these hats (and be a Figma guru, and create design systems, and…). More often, strategists are stronger in some of these areas than in others, working as part of a small tiger team that collectively notches expertise in them all, instead of as lone wolves. Even so, the most important role any design strategist fills in an enterprise is to own those two questions: “Are we solving the right problem?” and “Are we building the right solution?” Without those, none of the rest much matters.

Solving the Right Problems

Several months prior to reaching out to me, the client leadership had engaged an agency in Singapore to conduct broad market research around their pan-Asian customer base and offshore property investment. Focus groups and surveys revealed some very broad insights mainly orbiting the sales funnel: decision-making, response to advertising, buyers’ engagement with sales agents, what they thought of the R. Corp brand, and the like. Survey results illuminated how much money potential buyers had to invest in property, where they were placing that money, who they trusted with it, what kind of ROI they expected to see, and similar.

Some of this was useful. But as with most such non-ethnographic data, it did a good job of telling us superficially WHAT people think and do, but not WHY they think and do those things. Understanding the why is important if we’re going to create truly fit-to-purpose solutions. Was the client pointed at the right problem? More research was needed.

I therefore set about conducting one-on-one video interviews, occasionally with a translator, of a total of 19 customers — people who’d previously purchased an investment unit in one of their Melbourne properties. I talked to buyers who still owned their properties. I also talked to buyers who’d once placed earnest money on a client property in development but had reconsidered their purchase and pulled out.

What I found was far more nuanced, and interesting, than what I’d learned from the previous research. Five key insights stood out, several of which presented intriguing paradoxes:

Security: For buyers in places like China and Malaysia, a primary goal with their purchase is to move their money out of their home country to somewhere it could be protected from local corruption and market irregularity. They needed to feel certain of capital growth over time and a good ROI.Livability: Emotion played a large part in purchase decisions. Most foreign buyers wanted to identify with the property’s “livability.” From a design and facilities standpoint, the unit needed to be a place they would personally want to live in.Investors first: Despite their personal feelings about a unit’s livability, most buyers in Asia were pure investors who would never set foot in their Melbourne property to experience firsthand the design elements and service offerings, much less live in it.Easy, reliable rental management: It was extremely important to nearly all foreign buyers that their mortgage be covered by a reliable tenant. They did not, however, want to be bothered with the details of managing such rentals, especially in a foreign country. They wanted a “set and forget” solution.A cultural paradox: What Chinese (or Malaysian or Thai or Singaporean) buyers found appealing in an apartment was often markedly different from what their desired Australian renters would find appealing. As it happened, the foreign middle agents played a key role in helping potential investors understand the difference between what made for a desirable apartment in Shanghai or Kuala Lumpur and what did so in Melbourne.I discovered that what Chinese (or Malaysian or Thai or Singaporean) buyers found appealing in an apartment was often markedly different from what their desired Australian renters would find appealing.

I also spent a great deal of time in interviews with the client team, exploring the details of how this Australian developer does business. This included the sales, financing and closing journey, the construction process, communications with buyers, and their own internal operations.

We visualized these processes and ecosystems with with co-created artifacts like Experience Diagrams, Stakeholder Maps, Root Cause Analysis, and a wall covered with research data and observations.

Several critical insights became apparent here:

The time between the sale of a unit and the end of construction on the development itself may be as much as two years.A key client stakeholder, the contract administrator, knew that many prospective foreign buyers dropped out within several months of signing, receiving a full return of their earnest money. When we looked more closely at these drop-outs, we determined that figure was a staggering 48%. In essence, their sales team had to sell half of the planned units twice — and of those sold again, a further 50% of buyers also dropped out.Follow-up interviews with buyers who’d dropped out revealed their initial emotional connection to the unit had fizzled — it was an asset that existed only on paper and would not be completed for many more months, and about which they heard virtually nothing while construction was underway. That was a lot of time for anxiety and uncertainty to make them reconsider their purchase, especially with no penalties for dropping out up to six months after signing.A stakeholder map, co-created with the client, revealed that many prospective foreign buyers dropped out within several months of signing, receiving a full return of their earnest money.

All of this pointed to an altogether different set of problems and opportunities than what I’d initially set out to explore.

The original remit — eliminate the foreign middle agents from the sales process — critically misunderstood the role those individuals played in educating buyers, in creating a comforting and secure experience for them, and for hand-holding them through a deeply stressful process filled with unknowns. They also helped navigate the difficult and complex transfer of large sums (often of cash) from abroad to Australia.

The initial brief, in other words, would deprioritize and degrade the foreign customer experience in service of cutting costs deemed superfluous. The slice that middle agents took wasn’t a negligible sum, to be sure — but taken in consideration with what was being spent on selling half of their units 2–3 times, and the opportunity cost to overall sales if these agents were eliminated — suddenly it didn’t seem such an unreasonable figure.

It also became clear that there was ample room in the extended investor journey to engage with customers at a much more emotionally resonant level. Yes, these were ultimately “investment boxes,” as someone on the client team dismissively referred to the units they sold, but for buyers, they were much more than that: they represented an overseas home away from home, financial security into the future, a prestigious beachhead in a highly developed country, bragging rights, and much more. Leaning into that emotional connection presented an opportunity to keep investors engaged with their property even while it was still being built and thereby reducing costly drop-outs.

For foreign buyers who rely almost exclusively on friend and family referrals over advertising, too, it presented a far more effective future sales funnel. In fact, thinking of foreign owner/investors as a group instead of as disparate, disconnected individuals yielded interesting possibilities: a tight community of knowledgeable “owner-ambassadors” that could connect with & advise potential buyers might eventually serve many of the same functions that costly middle agents serve today.

It became clear there was ample room in the extended buyer journey to engage with customers at a much deeper level, keeping them emotionally, as well as financially, invested in their future property.

Building the Right Solutions

All good designers are problem solvers; all good strategic designers make sure they’re solving the right problem by asking “Why?” before leaping to solutions.

Asking “Why” in this case yielded valuable insights into the end-to-end investor experience, the role of middle agents, the deeper needs of buyers (emotional, functional, social), and even client financial operations. All of these insights presented opportunities that, with the right solutions in place, could represent improvements to P&L that more than made up for what the client spent on the foreign middle agents — whom it turned out were not nearly as superfluous as they’d appeared.

The client and I developed, prototyped, and tested several innovative solutions that leveraged these insights:

1. An engaging investor web portal and regular communications plan. Instead of going silent once buyers signed a contract, we aimed to make the client a trusted partner between buyers and their developing property in an accessible, delightful way that allowed them to see and connect emotionally with it throughout the two-year construction process. (For inspiration, we looked to the ways that the best hospitals and pediatricians help pregnant couples connect to their unborn child during the nine months of development up to birth.)

2. A social forum, attached to the web portal, that encouraged buyers to connect as a group, with the ultimate aim of creating and reinforcing excitement around the property as it became a reality. (A key issue for the client was concern around how a connected population of several hundred owners might conceivably turn to collective action against the client’s interests.)

3. Leaning into the work foreign agents were already informally doing by providing them with sophisticated, smartly designed assets — in print and online, with several language options — that helped buyers understand the “how” and “why” behind all interior design and service elements in their units and the building, and connecting those elements clearly with the needs and wants of Australian renters.

4. A simple, seamless, plug-and-play connection to Melbourne rental management companies who could assure buyers’ units were rented to responsible tenants for as long as they wished, in a manner that delivered a “set-and-forget” solution.

In a VUCA world, where nearly all competition is global and customer expectations change at the speed of TikTok, it’s not enough simply to have capable product teams. Every organization needs an innovation pipeline, but it won’t be found in your agile sprints. The key to spotting new market opportunities and staying ahead of the curve is making strategic design a priority.

This can be as simple as making a practice of what Jared Spool calls Strategic UX Research. It could mean bringing on a small tiger team of full-time strategists who work alongside product (and operations and HR and finance and marketing). Perhaps you pull in an agency or consulting strategist, if it’s a specific challenge, as above. And for big swings, creating and staffing a full-service innovation lab could have powerful follow-on impacts for collaboration, customer-centricity, and innovation across your whole culture, if done properly.

Whatever approach you elect, just make sure you’re solving the right problem and building the right solution.

Patrick Sharbaugh is a design strategist, educator, and consultant.

Is your organization solving the real problem? was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.