The over-emphasis on aesthetics in design is producing beautiful garbage

Artwork by @JPdoodling

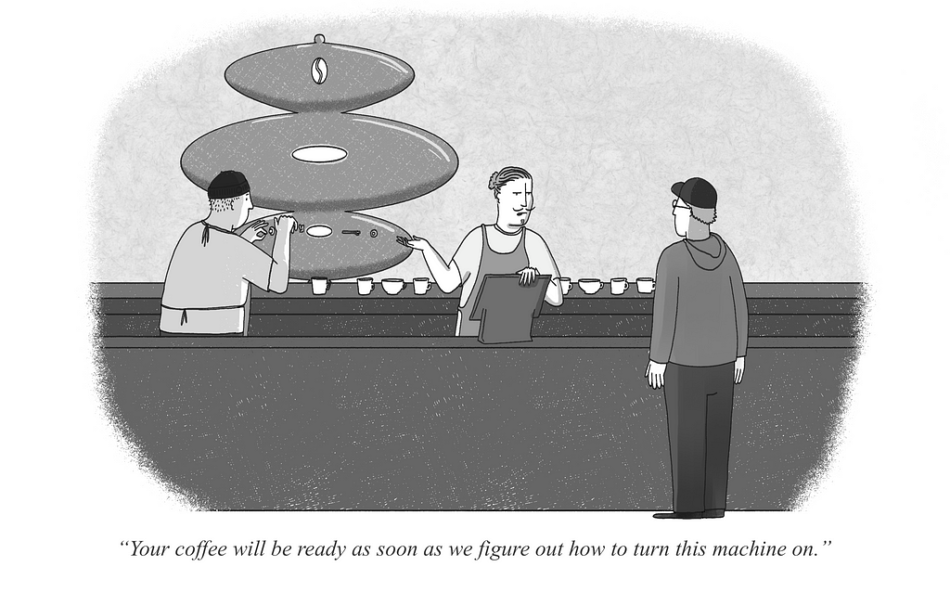

Two years ago, I made a terrible mistake. I purchased a coffee machine based entirely on how cool it looked. It’s really cool, like some kind of 1950s appliance crossed with a spaceship. Sitting on my kitchen counter in its powder-coated glory, it brought me joy just looking at it.

Until I had to make coffee. Then the problems began. If, like me, you assumed that you could use the carafe to fill the reservoir, you’d be wrong. It turns out that there was no physical way to tilt the carafe in such a way that it’d pour all of its contents in. The reservoir opening is so small that even in my most coordinated moments, I drizzle water across my counter, and still I have to dump the carafe’s excess down the drain. And don’t get me started on the controls. Any time I want to change a setting, descale, or really do anything except brew coffee, I find myself on google trying to figure out how to manipulate four ambiguously labelled buttons and a strange metal lever in order to get what I want.

Aesthetically, the coffee maker is a triumph, and yet it fails in virtually every aspect of its usability. Herein lies an important lesson about design. Aesthetics sell. But. When aesthetics become the primary consideration in design, users suffer. There’s a well-worn assumption that highly “designed” products are inherently better, simply because they’ve been more thoroughly considered by the designer. Surely working well is a foundational aspect of a luxury product!

In reality, this just isn’t so. Designers, intentionally or not, consistently deliver products and experiences that aesthetically impress, but just don’t work all that well.

That begs the question — whose fault is that? Is it the hapless consumer, throwing their money at every bevelled edge and bright colour? Is it business folk, knowing full well that their product needs to stand out in a saturated market of similar products? Or does the blame rest with the designers themselves for giving preference to the look over the function?

When you start to investigate this, the answer isn’t necessarily clear cut. There’s a lot of historical baggage that cuts both ways. Regardless, what’s clear is that the emphasis on aesthetics is frequently misplaced, and often distracts from what fundamentally is most important — quality.

It’s beautiful because it works?

A thought became crystallized in the early 19th century when architect Louis Sullivan– often called “the father of skyscrapers” — coined the now famous maxim “form follows function”. ¹

This quote-turned-design-principle essentially became law in modernist architectural and industrial design for the years that followed, prescribing that the design of any given thing should relate specifically to what that thing was supposed to do. Sullivan’s assistant took the idea and ran with it to some success, even suggesting that “form and function are one”. That assistant? Architect Frank Lloyd Wright.²

Sullivan’s Wainwright Building, St. Louis, Missouri, 1891. An example of his “form follows function” maxim. Photo Credit: LeMay, Warren. “Wainwright Building, 7th Street and Chestnut Street, St. Louis, MO.” Flickr, 23 Mar. 2023.

The turn towards function in modernism brought about its own aesthetic sensibility, carefully considering spaces, materials, and everyday objects to create things that were highly useful, but also beautiful as a by-product. To say these designers never considered form is misleading, certainly they would have, but the exploration of form would be to enhance (and certainly never supplant) the object’s usefulness. Modernists looked to the natural world, and found beauty there, evolved (quite literally) from functional requirements. According to them, when we see a bird and think it to be beautiful, we’re actually perceiving a form borne from its functional adaptations.

Modernist ideals of functional beauty made their way through the design disciplines, bringing us the International Typographic Style in graphic design (and with it, Helvetica), the “as little design as possible” electronics of Dieter Rams (whose influence is abundantly clear in the products Jony Ive designed for Apple), and taking foothold in the digital era with a user centred approach to interface and experience design.

Great artists steal. Rams and Ive design side-by-side. Photo credit: Tregoning, Axel. “Ive-Rams.” Flickr, 30 Nov. 2008.

That’s only half of the story though. Modernist functional beauty has always had one major problem. People.

People like pretty things

Some professional basketball players (All-time greats, like Wilt Chamberlain, Shaquille O’Neale, Giannis Antetokounmpo, come to mind), despite being generally excellent players, are just awful at shooting free throws. Shaq missed 5317 of them.

Another NBA star, Rick Barry, shot nearly 90% over his career, making him the NBA’s 4th best free throw shooter of all time. The catch? Barry shot underhanded.

https://medium.com/media/979657a9ffbf20a7755593285572daab/href

On his Revisionist History podcast, Malcolm Gladwell tells the story of how famously-good basketball player, and famously-bad free throw shooter Wilt Chamberlain was finally convinced by Barry to try his underhanded method. Chamberlain’s free throw percentage went way up, even going 28 of 32 from the line (underhanded) in his historic 100-point game. Despite this, Chamberlain would abandon the technique. Why? Shooting underhanded looks ridiculous. It’s derisively called “the granny shot”. Wilt, in his words “felt silly”. Humans, for all their ingenuity, still often prize how something looks over how something works.

This goes so far as to make humans associate function WITH form. If something looks good, then it MUST work well. A study performed by Masaaki Kurosu and Kaori Kashimura, researchers at Hitachi, demonstrated the so-called “aesthetic-usability effect”, wherein the “apparent usability is less correlated with the inherent usability compared to the apparent beauty”.³ I fell for it when I bought my beautiful, useless coffee machine. Those modernist ideals that form follows function can backfire on us, given that we’re programmed to assume that good form must mean good function.

The Chrysler car company learned this the hard way in 1934 when they released a new model called the Airflow, which employed streamlining in its design on the basis that a more aerodynamic car was a better car (a point on which the rationality is hard to argue). The car failed commercially, simply because it was too weird looking for consumers (At the time. Notable similarities in the Airflow’s design show up in the Volkswagen Beetle, one of the best-selling cars of all time). There’s a cultural factor in play with aesthetics, and while there’s no real top down enforcement of taste, norms form in a given culture, and people generally choose to conform to them, or to resist them. Form becomes a strong way of signifying that something is functional, accepted by the society you live in, and good.

The notion that form in-forms us about function is one that can be immediately exploited. Industrial designers, and their marketers picked up on this early, knowing that design would be a powerful tool for brand differentiation, and that different forms might appeal to different consumers with different aesthetic tastes. It did. But what about function? Is there a perfect form for a car, smartphone, ecommerce site? One that makes it perfectly functional? Maybe not, but surely some forms are more functional than others.

But if nothing else, it’s the form that does the selling. Now more than ever given the fact that more and more people buy things online, never holding them, feeling them, trying them, etc. Fast-fashion companies know this well, mining the runways for inspiration, and then producing cheap, lower-quality versions of the most captivating designs each season. If you’re spent any time on social media, you’ll likely have found that your feed is replete with ads for everyday products that have been given an aesthetic (and price) glow-up. You have to assume (at least from product reviews), that many of these designs are equivalent or worse in terms of their function. Still, this has become a highly successful business model for a select few. How could they possibly be non-functional if they look so nice? Why can’t beautiful things just work?

Phillippe Starck’s Juicy Salif, a gorgeous but useless juicer. Photo Credit: Alessi.com

Function, when it counts

There are, of course, spaces and places where function is paramount. Think about medical equipment, controls for heavy machinery, airplane cockpits, and anything to do with safety or emergency procedures (no one wants to throw someone a beautiful lifebuoy only to have it sink to the bottom). Appearance in these instances is secondary, or even ignored entirely. Culturally, we define these spaces as purely functional– at least for the operators.

The cockpit for an Airbus A380, a purely functional space. Photo Credit: Naddsy. “A380 Cockpit.” Flickr, 13 Nov. 2005, www.flickr.com/photos/83823904@N00/64156219/.

An important one is the accessibility space, where functional requirements are necessary to provide access for those with differing needs. An aesthetic decision might make text invisible to someone with low vision, or an entrance to a building insurmountable. One approach to accessible design is to jettison aesthetics entirely, which ultimately seems unfair to those forced to use the products (in recent years, the accessibility space has seen the emergence of companies offering more aesthetically-focussed designs–a welcome change).

A clash occurs when these functional spaces collide with secondary users, to whom aesthetics do matter. A great example of this can be found in GE designer Doug Dietz’s kid-friendly MRI machine designs. An MRI typically involves being placed in a confined space, being subject to loud noises, and requires the subject to remain as still as possible from a prolonged period of time; children were hard to scan, many found the machine to be terrifying, and often sedation was required . To remedy this, Dietz applied colourful vinyl decals to the walls and medical equipment, transforming the MRI scanner into a pirate ship. To accompany the transformed machine, Dietz and team crafted a script that placed the child in the centre of a seafaring adventure, complete with their pick of treasure at the end. The result? Fewer children required anaesthetic and higher customer satisfaction (GE now offers a variety of adventure wraps for their paediatric machines, each with a unique story).⁴ While the equipment the technicians use is purely functional, aesthetics still play a role for the people that the tools are used on. Sometimes you are a functional user, sometimes you are an aesthetic user.

The Adventure Series MRI, wraps the medical equipment in child-friendly decals. Photo Credit: GE Healthcare

But perhaps we overvalue aesthetics in many cases. It’s clear that completely functional interfaces work. And when they work well, we use them. A lot. Some of the most trafficked websites in the world are functional, and maybe even “ugly”. Google’s forays into more aesthetically minded design only followed its initial success, and even today, you might not describe a Google search results page to be “beautiful”. You could say the same of Wikipedia. Then of course there’s craigslist, an interface design that almost scoffs at the idea of aesthetics. But it works for what it does, and people use it. Despite being won over by aesthetics, one has to wonder if living a fully functional life would be easier, even if it is uglier. There are some people out there (dads mostly) who approach life this way.

Designers designing for designers

Designers themselves aren’t immune to the aesthetic-usability bias. Neither are other design decision-makers, from product managers all the way up to CEOs. Business-folks might not care about aesthetics, but they may not also care about functionality so long as sales are strong. While in a perfect world, finding the balance between aesthetics and function would be everyone’s job, in this one designers might be those best equipped to navigate such things.

But designers don’t always get it right. Certainly designing something that doesn’t work well to be aesthetically beautiful in order to fool people into buying it is (in my opinion) akin to a “dark pattern”, but I suspect that in the majority of cases, designers operate in good faith.

But just as basketball culture disparages underhand free throw shooting, designers are subject to their own insular culture– one which venerates beautiful designs. Design guru John Maeda describes an isolated design culture as a “microworld of aesthetic high-fives”.

Designers design for other designers, and those designers value “slick”, “clean”, “pretty”, designs. Designers should consider aesthetics, no question, and often you’ll see them (myself included) drawn to heavily aestheticized clothing, books, objects, etc (There’s a pencil case, and then there’s a designer’s pencil case). Designers, by the nature of their work, are more aware and more critical of designed things. While the design community was abuzz when Microsoft changed Word’s default font from Calibri to Aptos, it’s probable that most MS Word users either didn’t notice, or didn’t care. Some minor things that designers agonize over (like kerning) aren’t readily apparent to people who don’t know what kerning is. That said, when it all comes together, the overall effect is something that people like– they just may not know why they like it. In the oft-repeated words of Jared Spool; “Good design, when it’s done well, becomes invisible”.

Calibri and Aptos typefaces. Which is which? Most people don’t know. Image by the author.

The world of good design should be aesthetically beautiful, if it can be. Users want that. Where things fall apart is when designers take aesthetics too far. The shape of an object you’re supposed to hold makes it hard to hold. Interfaces obscure things from users because it makes things look “messy”. Clothing looks nice but falls apart after one wash.

Some might suggest that any aesthetic improvement that actively diminishes a product’s function should not be considered at all. The reality is more complex, with our culture, stakeholders, and biases in play, and a complex market to navigate.

Arriving at quality

Creating products that are both functional and beautiful IS possible. Just not easy. It requires an understanding of what role design should play. Those who get it, succeed.

“Most people make the mistake of thinking design is what it looks like…People think it’s this veneer — that the designers are handed this box and told, ‘Make it look good!’ That’s not what we think design is. It’s not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.’’ — Steve Jobs⁵

A good place to start is centering on the user. Usability testing– in any area of design– is crucially important to understanding how people make use of a product, and identifies major functional issues easily, with even a small handful of participants. Is your couch design comfortable enough for a whole netflix binge? Can you successfully navigate your smart home app to control your devices? Can you fill the coffee machine without spilling water all over your counter? Watch your users, and you’ll know immediately. This ensures that your product’s functional aspects remain intact.

Form shouldn’t be ignored either. Like any other design element, form is a tool. It demonstrates, facilitates, or even obscures a product’s function when it’s valuable. Form has a function. It can be decorative, or in many cases, specifically derived from function.

I own this amazing-looking Ettore Sottsass pepper mill. Does it work well? I’ve no idea. I’ve never used it. To me, it’s a sculpture. Photo Credit: Alessi.com

The best designers don’t treat form and function like they’re two distinct things. It’s not really a balancing act, so much as it is two sides of the same coin. In a truly great product, it’s hard to define where form ends and function begins. Stop thinking about how something looks, or how something works, and adopt an integrated mindset. If you end up designing a beautiful coffee machine that works really well, please send me one.

References

Sullivan, Louis H. (1896). “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered”. Lippincott’s Magazine (March 1896): 403–409.Frank Lloyd Wright Collected Writings: 1931–1939. Rizzoli International Publications, 1992.Kurosu, Masaaki; Kashimura, Kaori (1995). “Apparent usability vs. Inherent usability”. Conference companion on Human factors in computing systems — CHI ’95. New York, NY, USA: ACM. pp. 292–293.Kelley, Tom, and David Kelley. Creative Confidence: Unleashing the Creative Potential within Us All. London, W. Collins, 2013.Walker, Rob. “The Guts of a New Machine (Published 2003).” The New York Times, 30 Nov. 2003, www.nytimes.com/2003/11/30/magazine/the-guts-of-a-new-machine.html.

Rams, Dieter. “Omit the Unimportant.” Design Issues, vol. 1, no. 1, 1984, p. 24, https://doi.org/10.2307/1511540.

Gladwell, Malcolm. “The Big Man Can’t Shoot”. Revisionist History. Podcast transcript, July 6, 2017.

Maeda, John. “Design in Tech Report 2019 | Section 2 | about Design Organizations.” John Maeda | Design in Tech Report, 10 Mar. 2019, designintech.report/2019/03/10/%F0%9F%93%B1design-in-tech-report-2019-section-2-about-design-___-organizations/.

Is it good design, or does it just look good? was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.