A journey of design, beyond solving a complex problem.

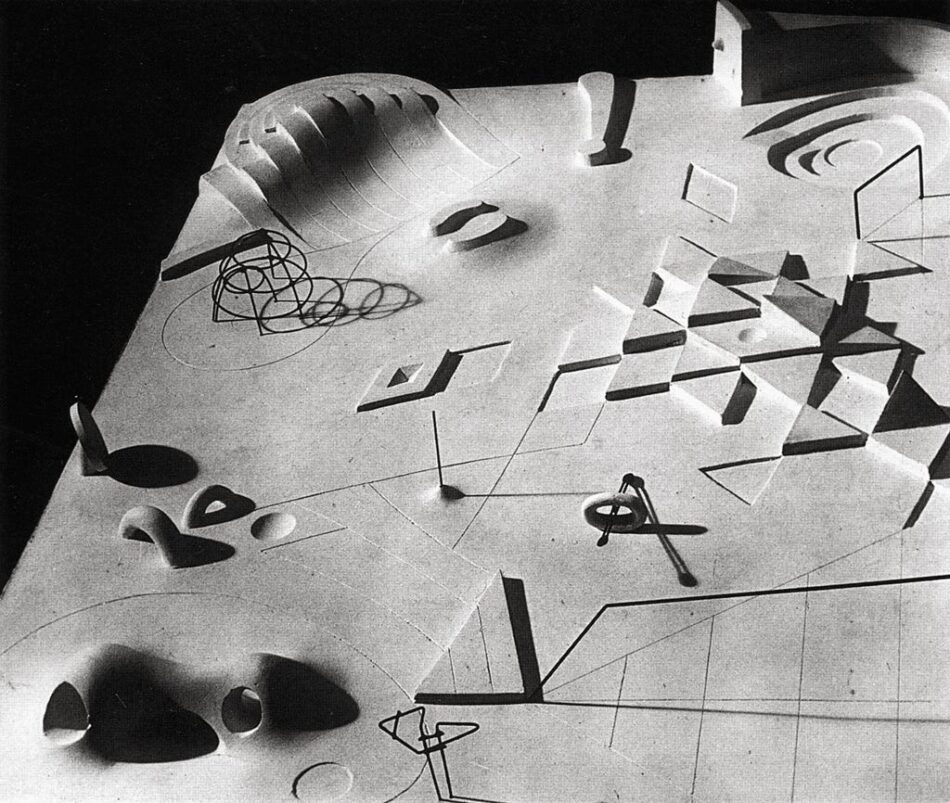

Noguchi’s art installation on his journey to find the design of public playground

When you think about playing, what comes to mind? Is it fun? Liveliness? Engaging with video games, laughing while playing a board game, or simply swinging in a park?

Play associated with non-serious activities that no immediate benefit (Bateson, 2014), in contrast to the challenges of complexity face up during the process of design. But the interesting part is:

What if design itself is a form of play?What if the process of solving problems is like an ongoing puzzle game, with rules, chance, and exploration?

We cannot view design as merely an activity for crafting things to look nice, drawing fancy images on a platform, or even generating AI-based pictures and writing more prompts to make them more beautiful. Design is not that easy. While the goal of design is to produce the best output, the journey to get there is a “long” and exhausting path to unfold effective and meaningful solutions.

This writing tries to understand the connection between design as a problem-solving activity, which evolves into a disentangled activity to navigate problems, play and playfulness as a way to make the design journey more pleasurable, turning challenges into discovery opportunities instead of getting trapped in frustration.

The evolution of design from crafting into liberal art of technology

First, we need to understand why design problems seem to become increasingly complex day by day. I get inspiration from Richard Buchanan (1992) for the term “design as a new liberal art of technological culture”. In the traditional sense, liberal art means a revolutionary transformation. Design began with fulfilling functional needs such as creating an artifact, painting, or propaganda poster (Buchanan, 1992). As society and culture evolved, so did design, it became a segmented profession, gaining exposure from technical and research knowledge, becoming a liberal art of technology. This means that design, as a creative skill, engages with technology, social culture, and human values, emphasizing the importance of design in shaping how we interact with technology and the environment.

Therefore, the fact that design roles are shaping society does not merely focus on aesthetics but also requires the ability to think holistically and integrate various knowledge areas. Design forms both an art and a science of putting things together. One of the main challenges designers face, impacted by this evolution, is to enhance their individual abilities to see the big picture from the social variables while also shifting to the details to connect patterns and comfortably staying in uncertainty to understand a wicked situation.

Design problem as a complex problem

Stad, the art installation in Groningen from Frans and Hansje Hazewinkel-Loos, aimed at visualizing the complex city information using a playful installation.

Can you imagine facing environmental issues such as food waste or wildfire? If these problems are too vague, consider the challenges when a brand designer needs to expand their product to a completely new and different target market, or an UX designer needs to create a persuasive design to increase product sales.

Isn’t it complex when they need to consider the cultural context of society, face fluctuating requirements, explore solutions while considering tight budgets, and connect psychological theory with hopes that their hypothesis leads to a successful outcome?

“Design problem as a wicked problem — the time of many problems occur, increasing complexity, rapid changes from the environment, and involving trans-disciplinary knowledge.” — Rebecca Price (2019), In Pursuit of Design-Led Transition.

Design problems have transformed into complex, wicked problems, or maybe they always were before we realized it — articulated as conditions that lack clarity and definitive solutions, meaning there is no stopping rule that says the problem has been “solved.” Instead, it is necessary to continuously rethink and adapt to updated conditions. Designers need to navigate these conditions themselves, applying an iterative process, which makes exploration not as easy as it seems, it can lead to feelings of frustration, overwhelm, and anxiety.

The star puzzle from Sherlock Holmes’s game, ruled to collect and connect all stars. Design activities seem similar: connecting the information and creating connections before choosing the final solution.

The nature of design activities can be defined as two major phases: problem definition — an analytic phase where the wicked condition is disentangled — and problem solution — a synthetic phase where designers explore potential solutions (Rittel, 1973). This concept is similar to the famous double diamond of the design process, in which the author divides the process into four phases: Discover, Design, Develop, and Deliver.

The design process continuously shifts between these phases, all iteratively while embracing ambiguity to unpack the wicked condition. Due to that condition, one crucial aspect of design activities is pattern recognition to find cross-relations. Edward de Bono, in his book Lateral Thinking, talks about establishing code communication as a mind language that can create a symbolic system that allows for understanding complex concepts in a simpler way. The designer’s task is to establish their own code of communication to help unpack wicked problems, seek patterns, and connect them with different variables. This system acts like a self-established framework that helps designers make sense of disparate information.

The play and playfulness

We understand play as an activity that produces pleasure and fun. Johan Huizinga (1949), the Dutch philosopher and author of Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture, defined play as a cultural phenomenon that is older than culture itself. It is something natural that humans do without needing to learn it. In practice, play goes beyond just physical activity; it evokes feelings of joy, tension, and satisfaction. Interestingly, play doesn’t necessarily have to be fun — it is pleasurable, which can come from serious or even dangerous activities (Sicart, 2014). In the six key principles of play, Huizinga mentioned that play needs to be temporary with specific approved rules, meaning players need to pretend in a created temporary sphere and within a limited time to complete defined goals. The goals need to be believed by everyone, such as the score in football — a translation of putting the ball into the opponent’s goal. Even the goals can be more abstract, like role-playing games with a purpose to explore different identities and understand different perspectives; players need to pretend to be someone else in a different context, which also enhances the ability to imagine different conditions.

Children’s Games painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1560), exhibited in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, showing kids playing 90 games in one picture. Can you mention at least 10 games played in the painting?

The activity of play evokes playful feelings — psychological, physical, and emotional perspectives regarding the activity. Scott G. Eberle (2014) identifies six play feelings: anticipation, surprise, pleasure, understanding, strength, and poise. These elements bring different emotions that make play enjoyable. For example, anticipation brings excitement as we look forward to what happens next, surprise gives us unexpected moments of fun, pleasure keeps us engaged with the activity, understanding evokes as we learn something new while playing, strength gives us confidence when overcoming challenges, and poise helps us stay calm while doing a task. These broad feelings contribute to a rewarding experience of play.

Design, play, and playfulness.

“Play and playfulness must be understood as essential elements in creativity as a whole.” — Irvin Singer, Modes of Creativity: Philosophical Perspectives.

So how do play and playfulness fit into the design process?

Let’s consider three aspects from the visual framework I developed:

Circular Playful Design Model by the AuthorPlay as an activity: Based on Huizinga (1949), play determines the rules to create structure and spontaneity. Similar to design, we engage with a set of constraints, either the problem to solve, requirements, business goals, budget, or time. Moreover, both play and design involve an element of pretending; in play, we create imaginary scenarios, take on roles, and pretend that, with those roles, we can achieve the goals. Similarly, in design, we use imagination to think about possibilities that aren’t there yet. Designers often need to pretend and imagine themselves as the user, thinking about how a product might be used, creating a user journey to fit the user’s context, and considering many scenarios when users engage with the product. This pretending aspect helps both play and design move beyond the current condition, requiring belief in one’s imagination.Playfulness as an attitude: Playfulness evokes due to the effect of play. Eberle mentioned that playfulness evokes six feelings — Anticipation, Surprise, Pleasure, Understanding, Strength, and Poise. These feelings evoked during play should also be involved in design. For example, anticipation mostly arises in the problem definition and problem solution phases, where designers try to explore edge cases of their product while asking questions to cover situations that might happen. Surprise in design comes when we find unexpected insights during the research process. Pleasure emerges after solving a problem effectively, seeing positive user feedback. Understanding arises during the process of learning user behavior, which can lead to better pattern recognition. Strength in design can be seen as experience; the more opportunities to unpack complex problems, the more designers can practice their skills. Meanwhile, poise is the designer’s ability to stay resilient when diving into the design process. Involving these playful feelings helps create a positive and resilient attitude, fostering an exploratory mindset.Design as a methodological approach: Design, as mentioned by Rittel (1973), forms two key parts of the journey — Problem Definition and Problem Solution. Throughout this process, designers need to juggle between analytical and synthetic parts. Designers need to be aware that the problem they handle is a wicked problem that requires thinking in layers. Solutions aren’t necessarily defined as good or bad, and this is similar to play — we learn from each move and adapt along the way due to different scenarios.

By embracing play in design, we are not only thinking about how to solve a problem but also rethinking the nature of the design process, including what attitudes we need to prepare for uncovering challenges. To delve into the details of how this concept suits the design process, I modified the double diamond model as a basis for the design process.

Circular Playful Design Model adapted to Double Diamond Framework

During the design process, from discovery and definition, which can be included in the problem definition phase, it’s often abstract and full of ambiguity. Designers attitudes of anticipation and understanding of the social context may help in searching for new patterns and meaning. Throughout the process, designers face ideation, which involves the attitudes of strength and poise to continue working in uncertain conditions to reach a solution.

This model visualizes how play can be a foundation to fill the design process with feelings of surprise, curiosity, and most importantly, joy.

Moving forward,

What if, instead of viewing design as a linear, “boring” path of problem-solving activities, we saw it as a playground?A sphere that we can explore, test, fail, laugh, and bounce back.

References

Bateson, P. (2014). Play, Playfulness, Creativity and Innovation. Animal Behavior and Cognition, 2(2), 99. https://doi.org/10.12966/abc.05.02.2014

Buchanan, R. (1992). Wicked Problems in Design Thinking. Design Issues, 8(2), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511637

Cross, N. (2006). Designerly ways of knowing : with 15 figures. Springer.

Eberle, S. (2014). The Elements of Play Toward a Philosophy and a Definition of Play. Journal of Play, 6(2).

Edward De Bono. (1992). The use of lateral thinking. Penguin.

Huizinga, J. (1949). Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. American Sociological Review, 16(2), 274. https://doi.org/10.2307/2087716

Price, R. (2019). In Pursuit of Design-led Transitions. Academy for Design Innovation Management Conference 2019. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332964016_In_Pursuit_of_Design-led_Transitions

Rittel, H. W. J., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01405730

Sicart, M. (2014). Play Matters. The MIT Press.

Singer, I. (2011). Modes of creativity : philosophical perspectives. The MIT Press.

Embracing play as the core of design was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.