Top 3 problems for designers: no research, no design strategy, and no career progression

Image by Matej Latin (Author)

It’s been a horrible year for design. Mass layoffs from 2023 continued and got even worse. AI is threatening to take creatives’ jobs, designers need to go through up to 11 rounds of interviews to finally land a job. Once they do, they’re asked to perform the work that would take at least two or three designers to complete.

Combine that with the learning from this report that only 1 in 5 designers have a future at their current company, and it all looks bleak. Is there a future for you in the UX industry? Is there a future for the UX industry itself? I decided to find out how happy designers are at work and unearth their most pressing problems. Only then can we start discussing how to fix these problems, and maybe even the industry.

My yearly Why Designers Quit report suggested that designers are unhappy with their managers and have no career progression opportunities. I wanted to see why they’re unhappy with their managers so the survey for this report focused a lot on managers and problems at work, alongside the general employee engagement survey questions.

751 designers responded to my survey. Those who work at medium-to-large companies will recognise most of the questions and their format. They’re statements where participants mark how much they agree (or disagree) with them.

49.9% of participants were UX/Product designers, 9.1% were web designers, 7.5% were UI designers, and 7.2% were designer generalists (Fig 1). The largest chunk came from the United States (17.6%), followed by 8.4% from India, and 7.7% from Canada (Fig 2).

Fig 1: Most participants were UX/Product designers (49.9%)Fig 2: Breakdown of where designers work

The distribution of seniority shows that many designers were high in seniority — senior and lead roles sum up to 68% (Fig 3). 31% of them were intermediate and 11% were junior.

Fig 3: 68% of designers were either senior or higher seniority.

Top 3 problems for designers

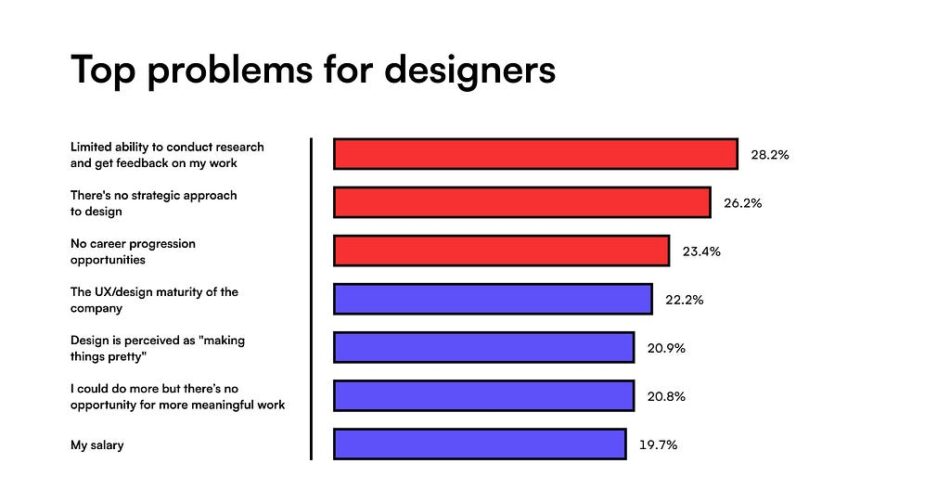

What are the three things you’re the most unhappy about at work? I ask a similar question in Why Designers Quit reports but with a key difference. There, I asked for the most pressing reason for leaving a job, here I allowed up to three answers. For designers, the top three problems at work are (Fig 4):

Limited ability to conduct research and get feedback on their work (28.2%)No strategic approach to design (26.2%)No career progression opportunities (23.4%)Fig 4: Most pressing problems for designers.

Low UX maturity (22.2%), design perceived as “making things pretty” (20.9%), and designers feeling they could contribute more (20.8%) and grow more (19.2%) are close to the top three reasons. A significant chunk also chose being the only designers at the company (14.4%) and having to work with multiple product/project managers (15.7%) as problems.

Here’s a quote from one participant that explains their situation, which will, sadly, resonate with a lot of designers:

Our designers are split by vertical areas and often left to fend for themselves. Research is severely lacking and the overall design strategy is often pushed back in favour of short term shareholder wins.

Many designers are stuck in producing low-quality design work (pushing pixels) because they work in environments where research doesn’t inform their work and it’s impossible to close the feedback loop which would gradually increase the quality of their product. Instead, a focus on quick, short-term wins is often favoured. Here’s how another designer described their current situation at work:

It’s pushing pixels in Figma when I want to work with real UX problems, new projects being promised and nothing, being asked for some extra graphic work sometimes, there’s just no way to grow and even though it’s been only 3 years as a UX/UI designer, I feel that my passion is slowly dying.

Let’s take a closer look at some of these problems and their potential causes.

Design leadership is lacking

The latest Why Designers Quit report showed that many designers are unhappy with their managers, 57% to be exact (source). That’s a significant number so I decided to investigate further.

Before I go into the report’s results, I want to look at what a good design manager is supposed to do. Hadrik Pandya provides a list of things, which includes (source):

Ensure a steady stream of challenging and meaningful work for you & your teamCommunicate timely & clear feedback to every team member

There are three more items on his list which we’ll get to later. So designers need timely feedback and challenging and meaningful work from their managers. Let’s see how they stack up.

50% of respondents said that their manager is not a good mentor and 27% were happy with the mentoring by their managers (Fig 5).

Fig 5: Designers aren’t happy with their managers’ mentoring.

When it comes to feedback, which is crucial to a designer’s work quality and growth, only 44% of the participants were happy with their managers (Fig 6). It’s more than those that were not happy with them (31%) but design managers really should do better here. 44% looks good at first inspection but because feedback is so crucial for designers, this percentage should be higher.

Fig 6: The majority of design managers are good at giving feedback.

When giving feedback to managers, 47% of designers feel confident to give negative (but constructive) feedback and 51% of the managers then take the negative feedback and improve (Fig 7). Again, these numbers seem high at first, but you’d expect more from someone who’s a manager, right? When you consider that giving, receiving, and growing based on feedback are among their main responsibilities, why are these numbers so low?

Fig 7: 47% of designers feel confident to give negative feedback to their managers, and 51% of those then act on it.

Only 1 in 2 designers feel confident to give negative feedback to their manager and only 1 in 2 managers that receive negative feedback will improve based on it. Putting it all together, only 1 in 4 design managers receive the necessary negative but constructive feedback and act on it.

So many design managers fail at the first requirement for being a good manager — giving and receiving feedback. How well do they do with providing challenging and meaningful work?

When asked whether their design manager is a good manager of design work, 45% of respondents weren’t happy with their managers and 31% of them were (Fig 8).

Fig 8: Design managers aren’t good at leading strategic design work.

Why do so many design managers fail at two crucial task of giving feedback and providing chances for meaningful design work? Slava Shestopalov provides an answer:

Design management is a vibrant spectrum, spanning from hands-on designers performing separate leadership tasks to full-fledged team leaders focusing solely on strategic design work.

We assume that because someone is a design manager all they focus on is their designers and leading strategic initiatives and projects. But that’s in theory only, many design managers are stuck in a spectrum somewhere between hands-on designer and design manager roles. And most of them are closer to the hands-on role than the design leader one (Fig 9).

Fig 9: A design manager’s responsibilities are on a spectrum between hands-on design work and managing people (Source).

One thing we have to praise the design managers for is trusting their designers and not micro-managing them. 71% of designers are happy with the trust their managers have in them, and interestingly, 74% of them feel they don’t need guidance from their managers and can work independently (Fig 10). I can’t help but think about the hands-on designer vs design leader spectrum mentioned above. Does this prove additionally that many (if not most) design managers are basically hands-on designers with additional responsibilities (and bonuses)?

Fig 10: Designers work independently and have the trust of their managers.

Lastly, I wanted to look at the hardest parts of being a good manager: being a good manager of people and recognising good work. 57% of designers who participated in the survey thought that their managers were good managers of people (Fig 11). That means they’re professional, empathetic, accountable, and good listeners. The number is relatively high, but if design managers truly were design leaders (instead of hands-on designers with extra responsibilities) shouldn’t they do better?

Fig 11: 57% of design managers are good managers of people.

Being a design manager entails that you manage strategic design work and people. Looking at the top-level responsibilities, that’s it. So why are there still more than 36% of managers who are bad managers of people? The tech industry’s view of who’s a top performer is primitive — they reward with promotions those designers who are good designers and those who know how to humbly brag about their achievements. The former are unlikely to be good managers and the latter are highly likely to be bad managers.

Here’s another interesting finding — 60% of designers who answered the survey thought that their managers recognised their good work and gave them credit for it (Fig 12). On the other hand, only 24% of design managers discuss career progression opportunities with their designers regularly (at least once per month).

Fig 12: Decisners are recognised for good work but have no career progression opprotunities.

How do we explain this paradox? Why are designers publicly recognised for good work but have no career progression opportunities? Does it stem from the design immaturity of the companies? Is it because design is unequal to engineering and product departments? Only 1 in 3 companies have a design leader at the top, 32% to be exact (Left side of fig 13). This is even worse in design-immature companies where only 22% of them have a design leader (Right side of fig 13). This finding hints at an imbalance in the product, engineering, and design trifecta.

Fig 13: Most companies don’t have a design leader with a seat next to the CEO.

A quote from a survey participant captures clearly what a lot of designers have to deal with when it comes to design leadership — many companies don’t have any of it but even when they do it’s simply lacking. Strategic decisions, even design ones, are taken by product or engineering leaders.

Just wanted to say that I’m currently a Product Designer II and we have a team of 2 including me. We both have same experience. A design manager would help me guide certain decisions which today is taken by product or engineering specific seniors.

No career progression opportunities

I had anticipated this would be among the most pressing problems because it keeps coming up in Why Designers Quit reports.

Returning to Pandya’s suggestions on what good design managers should do, the last item on his list was Create a personalised growth path for every member in the team.

He’s not alone in this suggestion. Cap Watkins suggests that design managers should manage every person’s career and check in on their professional goals every week (Source). Every week! When I worked at relatively design-mature companies we were supposed to discuss my career plan every month but we always ran out of time. The situation is dire for designers and their careers.

We already learned that only 24% of managers discuss career progression with their designers. It’s no surprise to see that only 22% of designers think that they have future and career progression opportunities at their current company (Fig 14). Putting it bluntly, 4 out of 5 designers don’t have a future with their employers. If they want to progress in their careers they’ll need to switch jobs.

Fig 14: Only 22% of designers think there’s a future for them at their current company.

(In)Equality of design

Can you imagine an established tech company without a CTO? Or without a CPO? No, right? So why does only 1 in 3 companies have an equal design leader at the top?

Inequality of design, compared to other departments manifests itself in the fact that 59% of designers work with more than one project/product manager (Fig 15). The ratio of designers and product managers should be 1:1 to have at least minimal chances of being equal partners (I’ve seen many cases of designers and PMs being 1:1 but designers still not being equal partners in that duo). Instead, only 1 in 3 designers works with a single product manager.

Fig 15: Most designers need to work with multiple product/project managers.

Ken Norton, formerly a partner at Google Ventures and head of product management at Google and Yahoo! looked into this and concluded that the ideal UX:PM:Developer ratio is 1:1:5–9. He elaborates on why the UX:PM ratio should be 1:1

When it comes to designers, I’ve preferred a ratio of 1:1 with PMs for user-facing product surfaces. Product teams work best when the dedicated triad of PM, designer, and tech lead form the core.

But most designers work with more than one product manager and 36% of them (the majority) work with three product managers or more. How do we expect designers to perform like that? How do we expect them to be equal partners to their product managers and prove their value at the same time? There’s no surprise that only 43% of designers feel equal to product managers and other peers (Fig 16). Considering in what circumstances designers have to work they’re doing ok. But with a lack of equality, these designers don’t feel confident to speak up when it’s time to discuss prioritisation, road map, etc.

Fig 16: 43% of designers feel equal to product/project managers and other roles.

If designers were equal to other roles, that percentage should be way higher. But it gets worse. Only 37% of designers have the privilege to work in dedicated design departments which helps conclude that design is an unequal partner in the tech industry (Fig 17).

Fig 17: Most designers don’t have a dedicated design department.

On top of that, only 40% of designers have design leaders (or at least creatives) as their managers (Fig 18). 21% report to a project or product manager, and 6% to an engineering manager. Can you imagine engineers reporting to a design manager? This helps explain why so many designers don’t have good design mentors or managers of strategic design work.

Fig 18: Most designers don’t have designers or creatives for their managers.

Conclusion: Designers are doing ok but need to ask for more

Designers need to fend for themselves. When they have a design manager, they can’t rely on them for strategic guidance or mentorship. Most don’t have managers with a design background. It all looks bleak when we also consider the inequality of design and how so many designers are stuck in their careers. But there’s a light at the end of the tunnel.

Considering all the negative findings of this report, designers are doing ok. They feel respected and valued by other team members and adequately challenged by their work (Fig 19).

Fig 19: Designers feel respected and that they’re growing as designers.

Even more uplifting is the finding that 61% of them feel that their work positively impacts business success and UX maturity (56%).

Fig 20: Designers feel their work has impact on business success and UX maturity of the company.

We’re not there yet as an industry. We stumbled in the last few years but we need to keep going. Designers need to ask for more from their leadership and themselves. If we want more we also need to show that we’re capable of more. Not more of the same, but more responsibility, ownership, and leadership from every designer, not just the leaders by title.

Did you like this post? Here’s how you can support me:

Designer engagement report was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.