Source: Papers, Please official Website’s Presskit

In today’s fast-paced political landscape, public outcry is swift and often fueled by a cacophony of voices on social media and other platforms. One particularly loud group has emerged, decrying various forms of media for being “too political.” This criticism is directed at various types of media: Movies, TV shows, music, and — of course — video games. These voices argue that entertainment should remain neutral, devoid of political commentary or bias when in reality all art and media are inherently political. From the themes they explore to the stories they tell, they reflect and influence societal values and issues.

For those of us who embrace the political nature of media and want to learn more about the different approaches games take to voice their critiques, I will analyze a few examples of how games achieve their creators’ desired effects. I will explore how video games can be used to critique societal norms, highlight injustices and encourage critical thinking about the world around us. Additionally I will discuss specific design choices that can help game designers effectively convey political messages, ensuring that their work resonates with players and sparks meaningful conversations. Throughout this analysis I aim to demonstrate that video games — like all forms of art — are essential for fostering political engagement and discourse.

In this series we will take a look at 3 different games and how each approached their goals differently. The first game we will analyze is Papers, Please (2013) by Lucas Pope.

Source: Papers, Please official Website’s Presskit

Glory to Artstotzka!

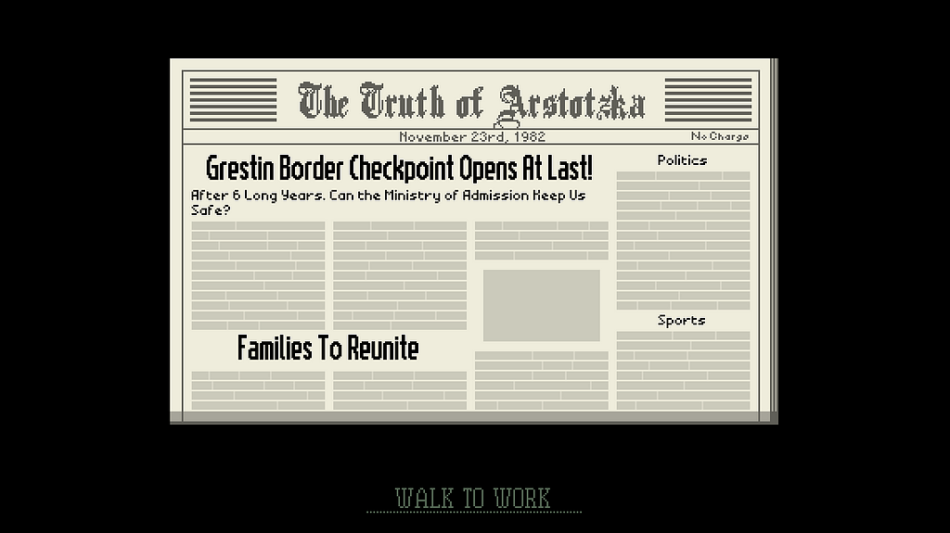

In Papers, Please players assume the role of an immigration officer in the fictional dystopian state of Arstotzka, reminiscent of authoritarian Eastern Bloc states such as the Soviet Union. The game’s setting is the border between Arstotzka and the equally fictional country of Kolechia in the city of Grestin, which is divided into two parts similar to Berlin during the Cold War. The game is set in the year 1982 shortly after the end of a war between Arstotzka and Kolechia. However political tension between these and other surrounding states remains high.

As an immigration officer, players must use various tools to determine which individuals are allowed to cross the border and which are not. The process varies from day to day and becomes increasingly complex as the game progresses. The game consists of 31 in-game days, during which players can process up to 15 applications per day if they work quickly. After each day players are shown a summary of the immigration officer’s living conditions including information about their current housing situation, family health and events in the country. Players also see how many immigrants they processed and how much they earned. For each correctly processed case, players earn 5 credits, but for each incorrectly processed case they receive a penalty.

After certain days, players must also make decisions about the officer’s personal life, such as which family member should receive medicine, whether to pay for food or heating when money is tight, or whether to buy a birthday gift for their son. If players have processed immigrants incorrectly during the day, their reduced wages are shown here. If this happens too often, they earn too little money to support the officer’s family, causing them to become ill and eventually die within a few in-game days. This creates pressure for players to process immigrants according to the orders.

Source: Papers, Please official Website’s Presskit

How Papers, Please works

At the beginning of the game processing immigrants is kept relatively simple. Immigrants from Arstotzka must be approved while all other individuals must be denied entry. Players must stamp each immigrant’s passport with an “Approved” or “Denied” stamp. This mundane task becomes more demanding as the game progresses with additional entry requirements such as verifying all data and documents, comparing weight and height, enforcing travel bans from certain countries, matching photos of wanted criminals and more.

Additionally, there are pre-programmed events that present players with moral dilemmas. How players respond to these events can significantly impact the game’s outcome and there are a total of 20 different possible endings. When one of these endings is reached, players must either restart the game from the beginning or return to a previously played day. The following are a few selected outcomes described in detail.

Source: Papers, Please official Website’s Presskit

On the 8th day of the game a hooded figure approaches the border control booth identifying themselves as a member of an underground organization called “EZIC”. Throughout the game this protest group assigns various tasks to the player who must decide multiple times whether to support the protest movement and risk being caught, or to continue their duty and betray the group to their superiors.

Source: Papers, Please official Website’s Presskit

On the 11th day of the game one of the arrivals leaves behind 1000 credits at the border booth. Players can choose to accept or burn the money. If they burn it the same person returns the following day with another 1000 credits which can be accepted or declined again. If players accept the money at any point their neighbors report them to the state in the following days due to the increased standard of living of the border control officer. Consequently on day 15 the officer is arrested on suspicion of connections to “EZIC”.

On the 12th day an investigator from the Arstotzkan authority visits the border booth and asks the officer for information about “EZIC”. If players admit to being contacted by this group the officer and his family are immediately arrested for treason ending the game.

If players decide on the 18th day to buy a birthday gift for their son he gives them a handmade drawing the next day. The officer’s son asks them to hang this drawing at his workplace. Players can choose whether to hang the drawing or not. If they do on the 20th day an investigator warns them and asks them to take down the drawing. If players comply they later learn that their son refuses to speak to them. However if the drawing remains hung on the 30th match day the officer is sent to a labor camp.

At a certain point in the game players have the opportunity to escape to the neighboring country of Obristan. To do this by the 31st day they must save 25 credits per family member and illegally confiscate an Obristan passport for each family member. If successful the officer and his family manage to flee.

Throughout the game the officer’s family may fall ill or starve as the player struggles to process enough cases to earn sufficient money for them. Players often face opportunities to accept bribes, feeling compelled to do so by their starving family. If the players do not earn enough money, the game also ends if all family members perish.

Source: Papers, Please official Website’s Presskit

The design of Papers, Please

Papers, Please examines the problems of an authoritarian state from a unusual perspective. Many other video games with similar settings often choose genres such as first-person shooters and similarly action-packed genres. For example titles like Wolfenstein and Dishonored critically engage with authoritarian states from such perspectives, where players typically embody the hero of the story who ultimately saves the world.

In contrast Papers, Please takes on a more restrained role for its protagonist. The player is not the action hero of the story but rather a simple border inspector. Their goal is not to overthrow the regime but to feed their family and — if necessary — to be able to leave the country. This narrative approach grounds the setting on a more down-to-earth level. Players experience developments in the country as they might in reality: through daily news updates and the stories told by arrivals at the border.

According to communication scientist Jonathan Cohen, it is plausible that the likelihood of identifying with a character in a medium increases when the consumer of the medium perceives themselves as similar to that character. (Source, p. 183–197) Therefore it can be assumed that immersion and identification in Papers, Please are greater than in other games with comparable themes, because players can better relate to a ‘normal’ worker than to an action hero who must shoot countless agents of a regime on their path. Cohen also writes that in terms of character identification, if empathy is a central part of this identification, it likely contributes to a greater reception of the messages conveyed by a medium. (Source, p. 259–261) Playing as a border inspector is thus not only relevant for potential gameplay mechanics and story developments, but right from the start it is crucial for the possible identification of players with the game’s protagonist.

Source: Papers, Please official Website’s Presskit

According to political scientist Dr. Jess Morisette the portrayal of bureaucracy in Papers, Please reflects socio-economist Max Weber’s understanding of a modern and rational state. Weber sees the development of bureaucracy — despite its advantages — as a fundamentally dehumanized system that strives for objectivity in decisions.

Bureaucracy therefore traps modern societies in what Weber refers to as an “iron cage” — a disenchanted world in which rationalization and intellectualization have replaced the interpersonal ties that once connected individuals to one another. (Source)

In Papers, Please players must act as quickly as possible to earn enough money by the end of the day to feed their families. They must ensure that they make no mistakes in any case, as errors are punished with wage cuts. Thus when playing Papers, Please one becomes part of the iron cage described by Weber in which individuals are mere cogs within a vast machinery.

What we can learn from Papers, Please

To simulate this machinery the user interface of the game was intentionally designed to be cumbersome, making simple tasks challenging. Through the complication of the interface players often find themselves rejecting border arrivals against their pleas and explanations, perceiving them not as people but as disruptions to the tasks.

However Papers, Please offers the opportunity to break free from this bureaucracy. It allows not only a literal escape by defecting to another country, but also a moral escape through various interaction options in the game. These choices between functioning pragmatically for the state or acting according to personal moral values echo Weber’s thesis that bureaucracies pursue a “Zweckrationalität” (instrumental rationality), while people want to act according to a “Wertrationalität” (value-oriented rationality). Allowing a refugee to enter despite missing documents to save them from a fictional death in their homeland, can be a player’s way to break out of the unnatural instrumental rationality and perform a morally satisfying action in line with value-oriented rationality.

While playing Papers, Please players are always free to decide whether to act in accordance with the system or their own moral compass. The pressure exerted on the players through time constraints and controls makes them feel both morally and systematically controlled. This tightrope walk makes playing Papers, Please an exhausting experience. The game thus not only simulates a system but also — to some extent — the moral decisions and states of mind of those living within it.

Final Words

First of all — thank you very much for reading. In the next part we will take a look into Spec Ops: The Line and how it uses altogether different techniques to communicate its message. If you enjoy my articles and would like to read more content like this feel free to follow me here or on LinkedIn.

The political and societal power of video games was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.