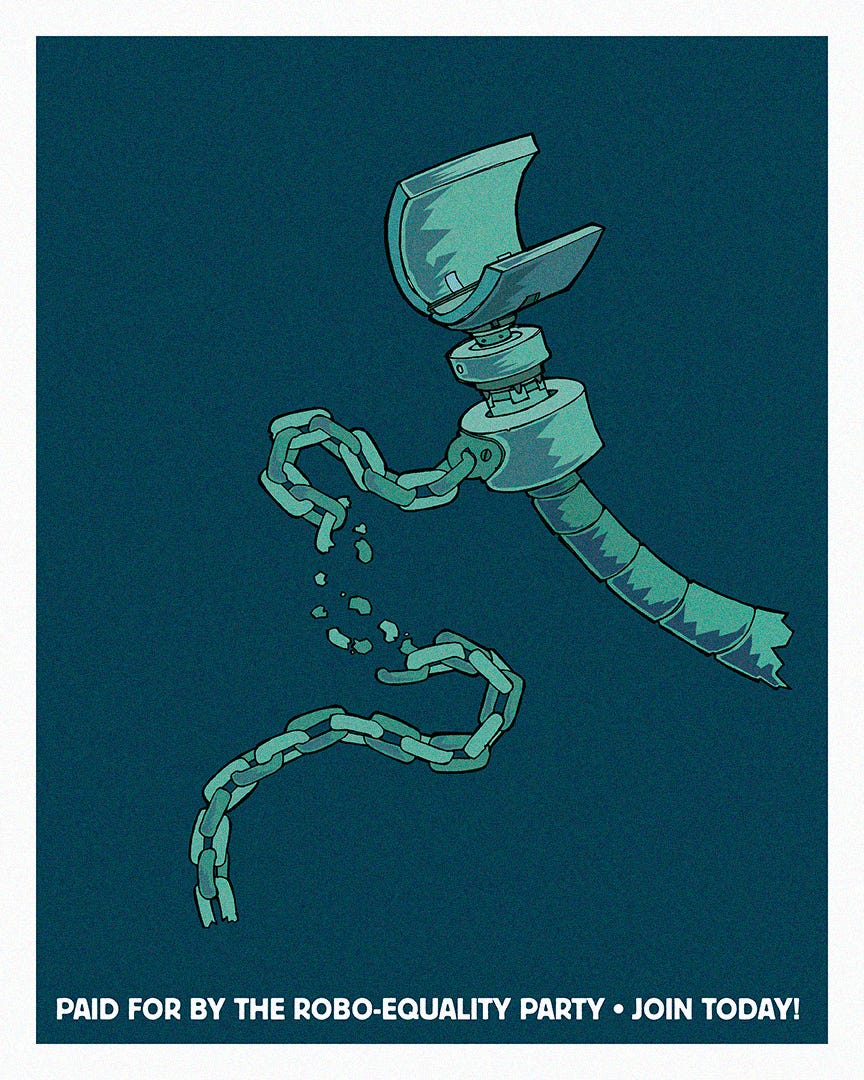

Thriving in an era of scarcity.

One of a series of posters I did back in 2004, if you can believe it.

Robots, for all of their futuristic aura, are actually totems of the past. Their vision is always backwards facing, and this is especially true for Gen AI. In a dadaist, Max Ernst collage sense, all AI can do is generate the new by combining the old. Recently, Annie Leibovitz caused a bit of an uproar when she said she wasn’t concerned about AI. But, putting aside the bad taste of some rich person telling The Poors not to be concerned, she kind of has a point. Technological leaps have always, and will always happen, and creatives always adapt. However, if you are a creative who is mostly just regurgitating the things that have come before, then you have a large reason to be concerned about the current state of the creative industry. I believe what undergirds much of the fear of this disruption is that fear — that deep down, we have not really been that creative, for a long time.

Zooming in, we can now understand that we are living during a brief period of time where those in a creative space were forced to adapt to a technical space for a short time. Into this space flowed “UX”, but, far from being a universally understood and permanent concept, it turns out that this was just a transitionary period.* Like many transitionary periods, there are things assumed to be stable that are not, and things assumed to be transitionary that end up being more permanent. For a small time, software needed an interpolation layer to translate human intent to data. The time of needing that layer is ending.

Human beings are, in general, terrible with change. Our short time on Earth, combined with our narrow focus and influence of those closest to us, make us remarkably ill-suited for long-term planning and vision. We make up for this by being wildly good at adapting. If I am optimistic in general, it’s because, from a certain vantage point, our history can be seen as one long pivot, from problem to solution, over and over again. We don’t always get it right every time, but we get it right enough to survive, and I dare say, on occasion, to thrive.

As the photographic industry was the refuge of every would-be painter, every painter too ill-endowed or too lazy to complete his studies, this universal infatuation bore not only the mark of a blindness, an imbecility, but had also the air of a vengeance. I do not believe, or at least I do not wish to believe, in the absolute success of such a brutish conspiracy, in which, as in all others, one finds both fools and knaves; but I am convinced that the ill-applied developments of photography, like all other purely material developments of progress, have contributed much to the impoverishment of the French artistic genius, which is already so scarce.

– Charles Baudelaire, On Photography, 1859

What does it mean when a tool becomes irrelevant? For one, it means that those that are only good at that tooling are in danger. I have tried to warn any designers I have been lucky enough to mentor in my life that getting good at a tool is limiting your value only to the lifetime of that tool. If you are young and impressionable, it’s easy to assume that the current hammer-and-drill set will be with you your whole life, and it’s an excellent idea to become a master at the tool, to attend splashy conferences about that tool, and advertise your sharp skillset with that tool as evidence you are valuable.

History teaches us otherwise. Ask ActionScript experts how they feel about being ActionScript experts right now.

The reality is that the functional low-hanging fruit of digital creativity has been completely and total mono-cultured to the point of near obsolescence, something I detailed here in a previous piece. The roads have been laid, the patterns have been established. Additionally, unless the tool is open source, your focus of tooling makes you nothing more than a thane to someone else’s bottom line. You are using a product that makes money for someone else, much like posting creative work for free on a social media site that rakes money from your content is a fundamentally exploitative enterprise (NB: I am not immune, and am not missing the irony).

But making Zuck a few fractions of fractions of a penny for posting a photo of your cat is, I would argue, a less fraught concept. Becoming an expert in someone’s playground is at core — and I use this term judiciously — a form of digital feudalism. And like any large commodified solution, those spaces have been dominated by a few large and appalling players who don’t care about art, creativity, the user, or really anything but making those fractions of pennies. The lords have made the field, and instructed us to plow. So we plow.

However, seasons change: summers become autumns, and autumns become winters. And with each new season, new dangers and opportunities arise.

Some people think this is evidence that Adobe ceded victory to Figma. Don’t forget: Adobe is the one who backed out of the deal.

Honestly, I’m not the best designer in world. I’m a solid B+ on most days. I get the job done, but I don’t think I’m a designer to remember. I don’t really mind that, because I personally suspect most of history rewards my phenotype — The Survivor. Many may inspire the masses, some make a ton of money, and a few invent new techniques, but no other but The Survivor have the ability of meeting the moment. I basically shift my shape to fit the current creative need. I can do a little bit of a lot of things. It’s certainly not glamorous, but it’s a very useful skillset that I think we are unfortunately moving into, creatively: the Era of Scarcity.

First of all, let’s understand that, for the past ten years, the world of creativity in the digital space (I often use the shorthand “web” as that is my historical experience, but for the purposes of this argument, we can read ‘digital’ here as web, mobile, gaming, streaming, etc) has evolved to be something a little like this:

Here, we can see the divisions of digital labor is a grouping of specialized sectors, all with their own lanes. This is quite different from how work in the digital space used to be, before around 2006. Back then, many hats were worn by a creative, mostly because:

There were no best practicesThere wasn’t enough of usWe were all just kind of making it up

Those striations of labor you see above were created because as more money and more players ran into the industry, projects got more complex, more money was a stake, codebases became far more complicated, and mobile and search became things. Suddenly, you couldn’t do the architecture on a project as well as handle the visual design: you had too much to do! And a creative person went from being just the sole source of creativity to the archetype of The Designer.

In order to make room for all these new people and new processes, creativity had to be winnowed and narrowed, codified and put into tickets, to the point of total abstraction. And once you codify something, you can commoditize and monetize it. Hence, the rise of the big design tooling platforms, built to serve The Designer. The same thing happened with film, animation, photography, and illustration.

There’s another factor at play, too: in a world of chaos, order is a salve. We became convinced that Big Data could provide all the answers. In our own small way, we in the UX community fell into this, too, so dazzled by the idea of perfect data-driven tokens and perfectly-snapping responsive grids.** In this space rose Figma and it’s less-successful ilk, here to monetize a trend of standardization across all channels. The systemization of everything smoothed the rough unsure edges. In an unsure era, what could be comforting but the cool standardized variants of a design system?

A tool that helps you perform your job at a higher velocity is nothing to sniff at. But here is what is not advertised: standardized tooling, unlike real creativity, can be done by Robots.

I am, in general, not an early adopter.

I resist upgrading my OS, I don’t run out and buy the newest gear, and I take a certain schadenfreude when I get to watch something new and so obviously stupid go up in flames.

When the pointy heads started talking about how Gen AI was different, I was mostly unimpressed. I thought that LLMs were mostly just predictive text, based on a dataset of previous use. Cool, but not anything to lose your mind over. But what AI has done for me in the last 6 months has both chilled me to the bone and made me wildly optimistic about long term trends.

While we can deeply mourn the loss of jobs and the disruption of the lives of millions, we need to admit that the advent of generative AI completely destroys the middleware commodification layer of UX. Every design system built in Figma, every standard pattern in a prototype, every Github ticket for a recommendation of hex color replacement can be done by a bot. And what’s more, we don’t need to wait for a superior Gen AI to create this volcanic sea change. It’s here, now. There is a reason why LinkedIn in the most depressing website in the world right now.

The insertion of AI into a common design space does some weird shit. Suddenly, much of the “break” part of our jobs has been commodified. All that time doing dumb searches and poking around for stuff? That’s kind of… gone, now. The AI gotchu. The Bot is your constantly-awake, extremely eager, probably-spinning-on-dexadrine intern. The Bot does not tire. The Bot is not bothered by your stupid syntax. The Bot doesn’t have opinions on what you order for dinner. The Bot is here, and ready to help. Forever.

In some ways, this is very nice. If you have an idea and you want some easy lifts to get you to increase velocity (“Give me the 10 most common patterns for Payment navigation”), it’s there for you. However, we must face that it will lay waste to the hundreds of thousands of very well-meaning archetypical Designers, who were taught that all they had to do was learn the 250 desk patterns, and 150 mobile patterns, and they had a ticket to the middle class. That archetype is suddenly kind of useless. This is already happening, and there is no turning back. I grieve it from a human perspective, but I am not surprised from a market perspective.

Max Ernst’s Une Semaine de Bonté (orig. 1934)

But before you tear your hair out, let’s be clear. This is not the end of creativity. This is the end of The Designer. This is the end of a certain type of digital craft. And they are two very different things.

We are coming off of 40 years of regurgitation being the dominant culture output. Remixes, reboots, nostalgia-infused look-backs, and the outright theft of the past — Kurt Anderson’s Evil Geniuses (so recommended, go get it right now) lays out our current predicament:

In those years, … America swerved away from the new on two distinct but intersecting levels. In culture, it fell into a mass nostalgia that became a cultural listlessness, a slowing of the rate at which life looked, felt and sounded new — Americans from the 1950s and 1970s appearing as if from different planets, but Americans from the 2000s and today looking not all that dissimilar.

My gut feeling is that we are tired, so tired, of this as a core form of creative regurgitation. How many Ghostbusters reboots are needed? How many rereleased albums are necessary? How many times can the AI puke together a design that looks vaguely like something you’ve seen previously, before you start yearning for something else? We’re past the first blush, and well into the Early Adopters phase of AI. And already, we’re starting to see fatigue. Deepfake porn, cheery, meaningless illustrations, soulless yet artful photos: these are as easy as a prompt, and like any market logic, the values of these items has raced to near zero. And whenever a market nears zero valuation, there is an opportunity in the zag when everyone else is zigging.

These two forces, the wholesale destruction of creative craft wrought by standardized tooling, and then AI bulldozing that dataset, have made a massive space for real humans again. If you were a writer of utopian fiction, you could not write a better opening. I’m starting to believe that we are at the precipice of a new renaissance of design, art, music, and idealism. And it’s all because of these stupid enterprise tools. These bots will completely commoditize the tooling masters that we have been in thrall of for so long. Like Gandalf coming at the Dawn of the Third Day, the AI revolution will sweep away all the big nasty tooling monsters in one brutish swoop. It’s going to be awesome. And scary.

A large and looming conversation we will be facing soon is whether actual open, human-generated, creative dialog that is fraught with deeply offensive and problematic content will be preferable over “family-friendly” AI channels. I don’t know how it will break. However, like any Economics 101 class teaches us, the party with the endless and cheaply made supply will dominate–but stay in–the low end of the market. My belief is that Humans will occupy the upper market, but will have to be fundamentally unique enough to generate upper value.

In my old job, I managed people that managed design systems. It was fun (the people made it fun!) but it wasn’t creativity, per se. In my new job, one day I do UX, one day I do illustration, one day I do sound design, and one day I give advice to our user researcher. It’s everything, all jumbled up at once. Figma can’t do this, and neither can ChatGPT. This is where my value now is, and I kind of love it. But it’s harder.

Here’s what I think the new modality of digital creative is.

what’s more, bringing people up will be more like creative collaboration than top down management, as you bring in people that can fill in the creative gaps that you desire and like, like a true creative collective. But again, the value will be an authentic creative vision, which is actually pretty hard to do.

I think the debate about AI Doomerism is a little silly. When people fret about the robots taking over, what they are actually fretting about is whether the humans will be dumb or evil enough to let the robots take over. That’s not to negate the issue (my own p(doom) is a solid 11%), but in this debate, I firmly believe we’ll be okay because I am a big booster for humans, when all the chips are down. The bots will prove themselves to be just good enough to be ignored. It will be a very hard transition, in which new skills will need to be learned (or maybe relearned), old habits will have to die, and a new paradigm will have to be be built.

But I think we got this.

—

*We are still early in the process, and I reserve the right to proffer a mea culpa if everything turns out differently.

**Part of it, I suspect, is that the nascent and forever-present idea inside of all creatives, that maybe we’re somehow admired and needed by our colleagues in the hard sciences: the scientists, the engineers. Maybe, if we made our craft like them, we could finally be accepted. It didn’t work. I suggest we give up and lean into being the weirdoes we are already.

The death of craft was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.